37 y/o female BIBEMS to ED s/p one episode of witnessed collapse while sitting and watching netflix at home with husband at around 3 pm. As per EMS, the husband stated that the patient’s whole body was shaking and he was unable to get a response from her during the episode. By the time EMS arrived the patient was arousable, followed commands, opened eyes on will, but was still disoriented. Upon arrival to ED, the patient’s GCS was 15 and is capable of fully participating in an interview.

History elements:

- Onset: 1 hour ago

- Quality: Terrible headache, was worse than anything I’ve ever experienced. It came on very suddenly.

- Radiation: Did not radiate, it felt like it was everywhere

- Severity: 10/10

- Timing: The headache started as I was watching tv with my husband, at 3 pm, I still feel the headache right now it has been consistent

- Recent travel: Denies recent travel

- Sick contacts: No sick contacts

- Pertinent positives: Headache, nausea, vomiting, loss of bladder control

- Pertinent negatives: Palpitations, weakness, numbness, recent head injuries, headaches, h/o strokes, dizziness, neck stiffness, fever, photophobia, visual disturbances, disorientation, confusion, weight loss, chest pain, SOB

- Past medical history: PKD diagnosed at age 35, HTN, denies any other

- Meds: Enalipril

- Family history: Denies any h/o epilepsy, cardiac arrhythmias, or intracranial hemorrhages

- Social history: Endorses 5 pack year h/o smoking, denies alcohol misuse, states that she is currently unemployed due to the pandemic

- Sexual history: Sexually active with one male partner, takes OCPs, does not use barrier protection, denies any h/o STIs.

Physical exam:

- Vitals: HR 76, BP 118/76, T 98.8 F, RR 18, SPO2 98%

- Head: Normocephalic atraumatic

- Eyes: Symmetrical OU with no ptosis, lid lag crusting, swelling. EOMIs intact, visual fields full by confrontation, PERLLA, no nystagmus. Conjunctiva pink, sclera white, no papilledema

- Nose: Nares patent bilaterally, no discharge, no active bleeding. Frontal and maxillary sinuses nontender to palpation

- Ears: No battle’s sign, no pain on palpation of external ear, canals non erythematous non exudative, TMs intact.

- Throat: mucous membranes moist, pharynx w no erythema

- Neck: No pain with ROM. No cervical lymphadenopathy. No thyromegaly. Airway patent, no stridor.

- Skin: warm, no rashes or lesions noted.

- Chest: lungs clear to auscultation bilaterally, unlabored respirations. Regular rate and rhythm, no murmurs, rubs or gallops S1 and S2 auscultated

- Abdominal: splenomegaly noted. Bowel sounds present in all 4 quadrants, tympanic throughout, nontender to palpation. Soft and nondistended.

Differential diagnosis:

- More Likely Differentials

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- “Worst headache of my life”, vomiting, seizure, syncope

- Most likely due to onset of sxs, description of sxs, and pmh of PKD

- Space occupying lesions

- “Worst headache of my life”, vomiting, seizure, syncope

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Less likely differentials

- Meningitis/encephalitis

- Headache, vomiting, seizure

- Less likely because patient afebrile, no neck stiffness, no persistent AMS, will still need to r/o

- Acute obstructive hydrocephalus

- Headache, nausea, vomiting

- Less likely because no papilledema, diplopia, strabismus, or persistent AMS

- Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

- Headache, seizures

- Less likely because no papilledema, focal neurological sequelae, persistent AMS

- Meningitis/encephalitis

Tests:

- Non-contrast head CT: white area in the center stretching into the sulci

- Lumbar puncture:

- Elevated RBC count, does not decrease from tube 1 to 4

- >2000 RBCs in tube 4

- Opening pressure >60%

- Elevated RBC count, does not decrease from tube 1 to 4

- CBC: WNL

- FBS: normal

- ESR and CRP: normal

- CTA to determine the origin of SAH

Treatment:

- Give nimodipine (60mg q4hr PO or NGT) and maintain euvolemia.

- Prophylactic antiseizure drug therapy, if necessary.

- Transfer to neurocritical care.

- Look out for complications such as hypoxemia, metabolic acidosis, hyperglycemia, elevated BP and fever.

- Measure cerebral perfusion pressure using the ICP and MAP. Maintain systolic blood pressure (SBP) <160 mmHg or mean arterial pressure (MAP) <110 mmHg.

- Aneurysm repair with surgical clipping or endovascular coiling within 24 hours.

Education/Counseling:

- Advise the patient that they will need to be admitted. They should get a CTA for further evaluation of the location of the bleed. Once the source is discovered surgical intervention would be needed.

- A subarachnoid hemorrhage is when bleeding occurs in between the layers of the brain. In this case this is between the arachnoid membrane and the pia mater. These usually occur spontaneously usually due to a ruptured aneurysm or it can occur after a head injury. Those with a history of polycystic kidney disease are more likely to have a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Most often a SAH will occur due to bleeding berry aneurysm within the circle of willis.

- There might be some neurological impairments that develop.

- There is a risk for developing epilepsy.

- There is a risk of bleeding to recur even after successful surgical intervention.

- Prognosis remains good for patient due to the level of consciousness they presented with, the lack of neurological symptoms, their age, and amount of blood on the initial head CT.

References:

- van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):306-318. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60153-6

- https://patient.info/doctor/subarachnoid-haemorrhage-pro#nav-3

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/aneurysmal-subarachnoid-hemorrhage-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis?search=subarachnoid-hemorrhage&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- https://wikem.org/wiki/Subarachnoid_hemorrhage

- PANCE Prep Pearls V3, Dwayne A. Williams

OSCE 2

A brief clinical scenario:

A 19 y/o male with a pmh of diabetes is accompanied by his father into the clinic. Patient presents with complaints of lethargy and weakness. Patient is not febrile. Heart rate is at a regular rate & rhythm. Denies any other associated symptoms. A fingerstick measurement of 59 mg/dl indicates that the patient is hypoglycemic. When inquiring about medication use and his last meal, the patient’s father states that it is Ramadan and that they are fasting. The patient was unable to eat for the past 27 hours. He had slept through the moment that he was supposed to break his fast. However he admits that he did take his medication.

Why it requires cultural awareness/humility

- This is a visit that is taking place during Ramadan, one of the holiest months of Islam.

- There are 3.45 million muslims in the US, the chances of encountering a muslim patient, especially in a metro area like NYC, is substantially high.

- Religion and spirituality are important factors in seeking care and in creating management plans. Anxiety regarding health is often reduced when taking religion into consideration.

- There are important differences in diet, modesty, privacy, touch, and even medications.

- Religious beliefs need to be acknowledged so the patient agrees with management.

- Many muslims, especially diabetics, will fast regardless of their health condition.

The cultural factors that need to be considered

- Fasting during the 9th Islamic month (Ramadan) is one of the five fundamental Pillars of Islam. Every year Ramadan moves back by 10 days, it can occur in any of the four seasons. This results in variations in the number of fasting hours.

- Muslims refrain from oral or intravenous substances from sunrise to sunset. Some even abstain from using topical eye or ear drops, rectal suppositories, or enemas. Nasal drops/sprays are permitted as long as the residue does not reach the back of the throat.

- There are misconceptions about the etiologies of diseases, some will abstain from medications believing they are in good health.

- Muslim patients will often ask for same-sex providers. Some customs can prohibit handshakes or any contact between genders.

- Preservation of life overrides religious guidelines especially in a life-threatening situation.

- Prayer occurs 5 times a day. Bedridden patients may choose to pray in bed. Overall a prayer can take a few minutes, so providers should be patient.

Any beliefs that might be different from western medicine beliefs or unique considerations that care of this patient might require

- In western culture there are diets that support intermittent fasting but still support intake of water to prevent dehydration. Catholics often give up meat on Fridays during lent. However the length of time fasting is not as rigorous as that of Ramadan.

- Some Muslims consider this time of fasting as a great opportunity to make healthy changes. If practiced appropriately, fasting and having a balanced diet, can lead to weight loss.

- Health is considered to be a gift from God and is considered an individual’s religious duty. Suffering and disease are seen as punishment or as a challenge from God. Overcoming such hardship through prayer and seeking medical treatment can resolve one’s sins.

- Honey in western medicine has been noted for its antimicrobial properties. It is also recommended in the Quran. Many Muslim diabetic patients use honey as a traditional remedy.

Areas where conflict might develop

- Conflict may develop if the provider is unaware of the customs that a muslim patient follows.

- Provider is unaware of the meaning of Ramadan and practice of fasting from sunrise to sunset and becomes upset with the patient.

- Patient is fully compliant with DM medications, but only takes them during certain hours. This could lead to misunderstandings because the provider might assume that the patient is taking medications appropriately.

- Provider is not aware of any of the recommended dosages for Muslim diabetic patients during Ramadan.

What would be expected of the student in demonstrating Cultural Competence/Humility – what things would the student be expected to say/do/avoid/suggest/consider in this scenario (these may not all be relevant)

- The student should introduce themselves and refrain from initiating a handshake unless the patient does it first.

- If the patient requests a provider of the same biological sex then, the request should be fulfilled if it is possible.

- The student should be knowledgeable about the dietary restrictions that the patient is following during Ramadan.

- The student should acknowledge the importance of fasting according to the patient’s faith and be willing to formulate a plan that the patient will follow.

- The student should listen to and acknowledge the patient’s understanding of their illness. The student should offer their medical opinion with consideration to the patient’s beliefs

Any patient counseling or education that would be required in the situation

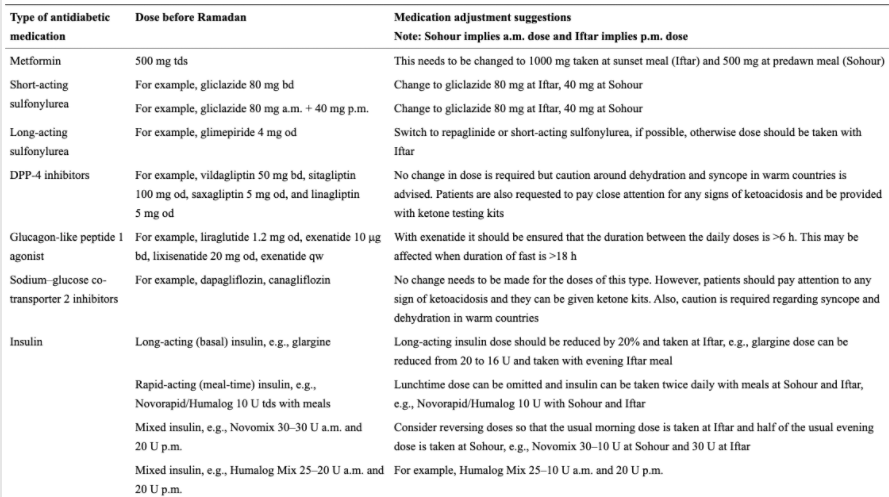

- Modifying the dose of antihyperglycemic medications is an essential component of managing patients with diabetes in Ramadan

- Recommend

- Regular glucose readings daily

- Meet with PCP one month prior to Ramadan to discuss potential medication changes (see table below)

- Avoid large heavy meals or vigorous physical activity when breaking fast

- Break fast if hypoglycemic symptoms appear

References:

- Attum B, Hafiz S, Malik A, et al. Cultural Competence in the Care of Muslim Patients and Their Families. [Updated 2021 Jul 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499933/

- Swihart DL, Yarrarapu SNS, Martin RL. Cultural Religious Competence In Clinical Practice. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; July 23, 2021.

- Abolaban H, Al-Moujahed A. Muslim patients in Ramadan: A review for primary care physicians. Avicenna J Med. 2017;7(3):81-87. doi:10.4103/ajm.AJM_76_17

- Almansour HA, Chaar B, Saini B. Fasting, Diabetes, and Optimizing Health Outcomes for Ramadan Observers: A Literature Review. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8(2):227-249. doi:10.1007/s13300-017-0233-z